In previous times traditional sailing canoes were important in most of the island groups of the tropical Pacific.

During the 20th century however, much of the traditional sailing heritage has been lost and sailing craft are now only common in a handful of locations, such as the Gilbert Group, outer islands of Tuvalu, and in the Western Caroline Islands.

One area where sailing is still very much alive is the Lau Islands in the east of Fiji. The Lau Group consists of almost a hundred islands and reefs sprinkled in a north/south line about half the distance between Fiji’s main island of Viti Levu and the Kingdom of Tonga.

In many respects the islands of Lau are a transition zone between Fiji and Tonga. Geographically, ethnically, and linguistically the area has elements of both the Polynesian Tonga and the more Melanesian Fiji. This is likely to be the result of the original Melanesian inhabitants having sporadic contact with Polynesians through settlements, wars, trading, and drift voyages. From north to south the Lau Islands stretch over 250 nautical miles.

The distance between the islands is usually less than 30 miles and most rise higher than 100 metres. From a sailor’s perspective, these factors simplify navigation in the area and result in the islands in Lau being a large “target” when sailing to them from a distance. Considering this, the meaning of the word “Lau” in the local dialect, “hitting the target”, could easily have its roots in canoe voyaging.

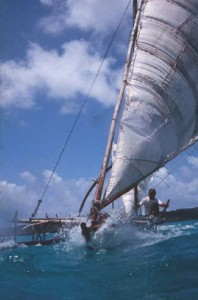

The sailing canoes that exist today in Southern Lau are known as “camakau” or “camakacu”. The typical camakau of today is approximately 7 to 9 metres in length and carries a single sail of the oceanic lateen type measuring about 27 square metres. The craft is single outrigger in design, with the outrigger (“cama”) being about 60% of the total length of the canoe.

The main hull of the canoe has a round bottom and is made from a dugout log. Strakes are attached to increase the freeboard and a deck is added to make for a convenient working platform and to reduce the amount of water finding its way into the bilge.

In the comprehensive reference “Canoes of Oceania” the authors describe the camakau in 1925:

“The Fijian camakau, the great outrigger used for travelling about among the islands, and particularly for paying visits to friendly chiefs, shares with the Micronesian “flying proa” the distinction of being one of the two finest types of sailing outrigger canoe ever designed”.

The camakau appears to be a product of Micronesian and Polynesian technology applied to the hardwood resources of Lau. It is generally agreed that sail rig is Micronesian, probably introduced to Fiji via Tonga sometime in the 1700s for its superior windward sailing ability. Oral tradition and historical accounts from early travelers point to Tonga and Samoa for the origin of the canoe itself.

In the late 1700s a carpenter from Samoa, Lemaki, was sent by the King of Tonga to build canoes in Lau where he eventually established a clan of canoe builders which persists to this day, especially on the island of Kabara. A Fiji historian, F. Clunie, states:

“The Fiji connection revolved entirely about vesi timber. Tonga leaders sent their Tonga and Samoa canoe builders to Fiji to exploit this resource. The development was stimulated – even expedited by the introduction of metal tools to Tonga, which made exploitation of vesi hardwoods on a grand scale more feasible.”

Although there are four types of wood which are sometimes used for the hull of the camakau, the preferred wood is vesi (Intsia bijunga). Sometimes known as greenhart in English, it has characteristicssimilar to the teak of southeast Asia. Vesi trees grow in extremely rocky areas and sometimes appear to grow straight out of solid rock.

To the casual observer it is somewhat puzzling how these trees manage to grow in areas of such poor growing conditions while they are not found in more fertile areas. One possible explanation is that these trees have minimal water requirements and can tolerate dryer conditions than other species that would normally out compete the vesi.

Like the sailing craft from Micronesian islands to the far north, camakau are always sailed with the single outrigger to windward. When proceeding upwind, a camakau will change course across the eye of the wind. On a modern yacht this maneuver would be known as “tacking”, however it is different procedure on a camakau and technically known as “shunting”.

In shunting (“cavu” in the Lau dialect) the steering paddle at the stern is moved to the bow and the tack of the sail rig is taken to the stern. The “bow” effectively becomes the “stern” and viceversa. The outrigger remains to the windward side to compensate for the force of the wind on the sail.

Camakau, like most outrigger craft, can capsize. The usual cause of an overturned canoe is an excess of wind in the sail combined with another factor, such as the main sheet jamming, a weight shifting on deck, an unexpected wave, or the outrigger becoming detached. To right a capsized canoe close to shore, the crew simply drags the craft into shallow water and raises the outrigger over the main hull.

Offshore it is more difficult. Because the positive buoyancy of an outrigger presents less of an obstacle than its weight, the crew will try to sink the outrigger so that it passes under the main hull. This can be done by a combination of standing on the outrigger, and pulling underwater from the direction of the main hull on a line attached to the outrigger.

Sailors throughout history have admired Camakau.

In 1840 a United States Naval Officer, C. Wilkes, wrote of a camakau 30 metres in length that required 40 men to sail it. He stated, “it’s velocity was almost inconceivable”. J. Hornell noted: “The pace at which these magnificent canoes tear along with the wind on the quarter has evoked the admiration of all who have seen them.” Others have stated that speeds of 14 to 15 knots are often achieved.

Within the period covered by the memory of sailors alive in Lau today, trips in camakau were usually confined to visits to other islands in Lau and occasionally to Fiji’s capital, Suva. Even very old residents can recall only one incident of a canoe voyage from Tonga: in about 1914 a canoe was sailed to Moce Island by eleven convicts who escaped from prison in Tonga.

The canoe was about 14 metres in length and Moce residents recognized it as one built some years earlier in Fulaga. The distance from Southern Lau to Suva is about 200 nautical miles. In the past half-century the trip has apparently been made by camakau on two occasions. In 1953 two canoes from Ogea and four from Fulaga sailed from those islands to Komo, Lakeba, Vanuavatu, Moala, Gau, and finally to Suva for an official visit made by the Queen of England.

Eleven years later in 1964, a fleet of four Kabara canoes sailed to Totoya, Moala, Gau, and Suva for a Methodist Church celebration. Between Moala and Gau one canoe was swamped by a large wave. The crew members were picked up by the other canoes, and the disabled camakau was abandoned.

Canoe navigation in most areas of Southern Lau does not present major challenges due to the small distance between islands; the target island can usually be seen before the island of departure disappears. The exceptions are the trips to Vatoa and Ono-I-Lau. Elderly residents of Ogea explained that for a trip to Vatoa, landmarks on Ogea hills were used to establish a course. Shortly after these disappeared over the horizon, Vatoa would appear.

For the future of sailing canoes in Lau, the wood resource is an issue. One reason for constructing camakau in Southern Lau was the availability of vesi timber on Kabara, Fulaga, and Ogea.

The present commercial production of vesi wooden bowls, especially ‘tanoa’ (bowls from which the traditional drink ‘kava’ is shared), from these islands is affecting the supply of vesi for canoe building. Records show that over 100 tanoa per month are exported from the island of Kabara alone. The labour situation is also a consideration. It can easily be understood why skilled woodworkers who are engaged fulltime in the manufacture of wooden bowls for cash income are reluctant to spend time in the building of canoes, which are rarely sold.

It is likely that events in the outside world over which the residents of Lau have little control, such as the price of fuel and other commodities, remittance income from relatives, and the money earned from the export of ‘tanoa’, will have a major effect on the persistence of the traditional sailing craft of Southern Lau.

By Robert Gillett

Kira says

Hello, first I want to thank you for taking the time to read and respond to this message. I was trying to see if there is a business located in Fiji providing a tour on one of the traditional sailing canoes. My family would really like to take a ride on one. Any links or information you can provide would be greatly appreciated. Thank you and have a great day.